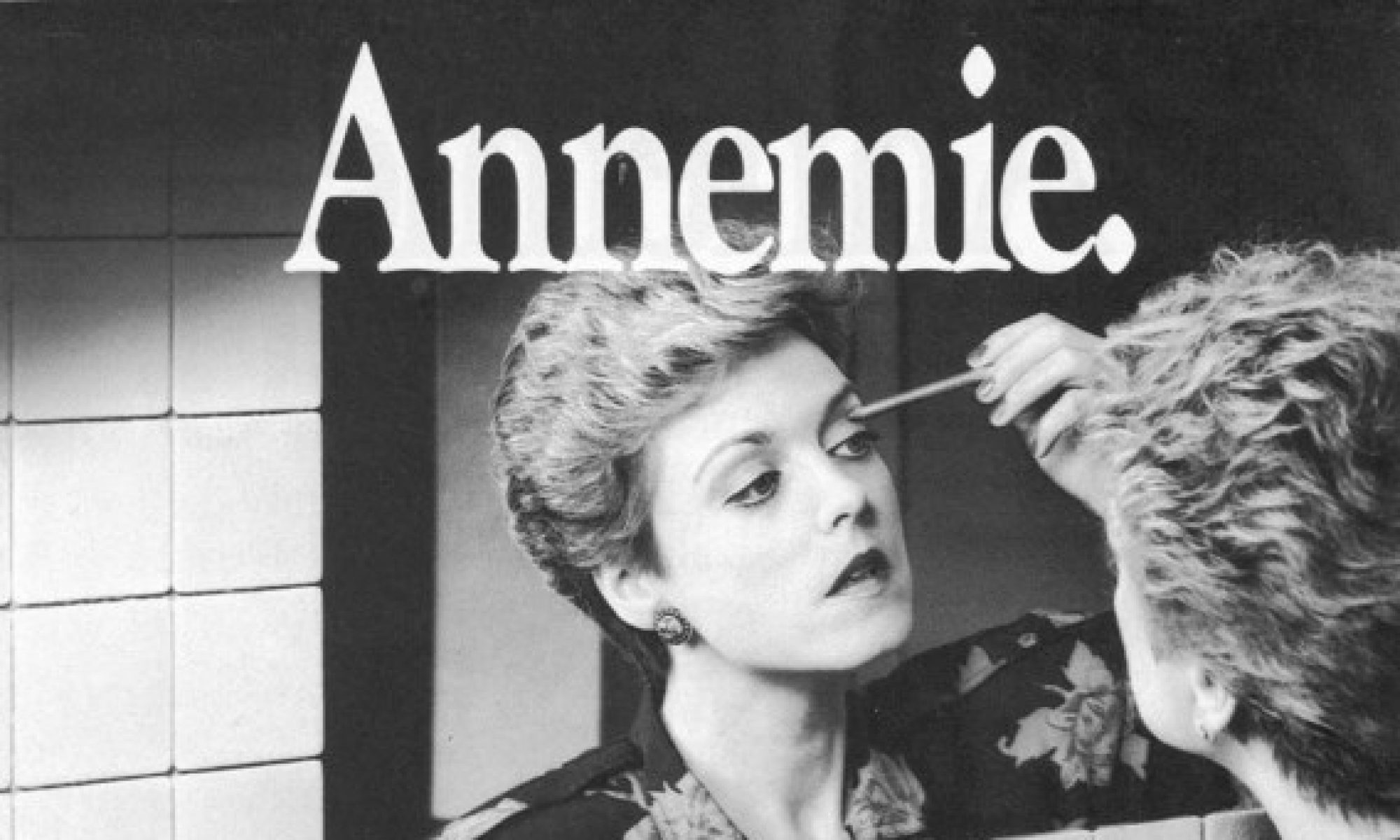

Afgelopen ELDR congres in Palermo was Annemie Neyts haar 6de en laatste congres als voorzitter van de Europese liberale partij. Aan haar de eer om het congres te openen.

Dear Presidents, Leaders, Ministers, and Members of Parliament,

Ladies and Gentlemen,

Dear Friends,

It is my honour and pleasure to officially open the ELDR congress in Palermo, which is the sixth and last congress of my tenure as ELDR President. The realisation that an important chapter in my political life draws to a close fills me both with regret and joy. Regret because a wonderful period of hard work ends, and joy because of all the friendship and support I enjoyed during those six years, and hopefully will continue to enjoy in the years to come. Believe me: it is a good thing that our statutes limit the membership of the ELDR Bureau to a maximum of three successive terms. If this wasn’t the case I am indeed afraid that many of us would carry on way past the limits of our members’ endurance, because it is such an challenging and fulfilling undertaking to help shape European Liberalism.

Dear friends, before turning to the future, I have the sad task to ask you to share in the remembrance of two great Liberals who died in the last few months.

David Griffith was for years the devoted treasurer of successively Liberal International and ELDR, paying minute attention to our financial health and sustainability, and enlightening us with his vast wisdom and experience. His health had deteriorated these last few years, but he continued to come to Brussels as long as he possibly could. He died in August and will be regretted dearly by all of us.

Willy De Clercq was among the founders of ELDR in 1976, and was elected as its President in 1981. He remained our President until he resigned to become EU Commissioner for Foreign Trade at the end of that year. In that capacity he played a key role in opening up the world markets to European goods and services. In the meanwhile, he had presided over the adoption of the ELDR election Manifesto for the second direct elections of the European Parliament. When his Commission mandate ended, he resumed his participation in all major ELDR events, and so it came about that we could persuade him to run for the Presidency at the eleventh hour during our 1990 Congress in Ireland. He was duly elected and remained our President until 1994. And again he presided over the adoption of an election manifesto this time for the 1994 direct European elections.

I must confess that we gave him a harder time than you ever gave me during our congresses, but he always remained his kind, wise and benevolent self.

Willy De Clercq has been one of our strongest supporters through all of those years, and many of us keep the fondest of memories of his wife’s and his participation in so many of our events.

May I request a minute of silence in remembrance of our two friends?

Thank you.

Dear friends, we are assembled in Palermo, the capital city of an island that has played a key role in European and World history. As Leoluca Orlando reminds us, this is not only an islands graced by the Gods of Ancient times, it has been for centuries a meeting point of cultures, languages and religions. Alas, it has also been a battle field for most of the European dynasties.

It is also the unforgettable backdrop of Lampedusa’s classic novel “Il Gattopardo” in which the old patriarch says “everything has to change so that everything can remain unchanged.”

I don’t know whether that also applies to Europe, and maybe it does, more than we suspect. In any case, it is fitting that it was on this very island, in the city of Messinathat the foreign ministers of the six founding nations of Europe decided to launch the European Community. That momentous meeting took place in 1955. Two years later, in Rome, a Treaty was signed that indeed established a European Community.

The speed of it all was astonishing, especially if we contrast it with the painfully slow pace of the most recent institutional and regulatory adjustments. Some observers will remark that changes take longer when 27 members are involved, rather than the original 6. Unfortunately the gravest divergences occur not among the 27 member states, but precisely among the founding 6. So size is not the explanation. Then what is?

If we look back at the fifties, we should realise that the founding fathers anticipated on the impending changes and realised that they needed to unite better in order to withstand the challenges and threats that surrounded them. One was the irresistible economic growth and expansion of the United States which was a challenge, not a threat, and the other was the rise of the Soviet Union and the Iron Curtain that had been cruelly drawn right through the heart of Europe, a severe threat if there ever was one.

I would daresay that this spirit has survived through the decades, right until the resounding NO on the referenda in Denmark, France, Ireland and the Netherlands.

These days we are submerged under a tsunami of laments and articles by economists, political scientists, philosophers and other pundits who write that they had known all along that the Euro zone was a misfit and would never work; Paul Krugman, Noble Prize laureate, foremost among them.

I say, it is high time that we stop these laments, that we squarely face the situation and start doing something serious about it. The succession of small steps, each of them too little too late, should stop. If ever it was the moment to do something really bold, it is now. Several of our member parties are in government; the single largest ideological group in the Commission is formed by liberal commissioners. Together, we must lay the foundations for a renewed Union which succeeds in properly rebalancing the member states and the institutions of the Union. We are in this together; we should rescue ourselves before it is too late. And we can achieve this, if we start by looking soberly at the facts. The first fact I want to bring to your attention, is that the Euro currency is still, perhaps amazingly to some, going strong. The Euro still stands at about 1,35 dollars. It stood at 0, 87 dollars when it was introduced. May I point to the fact that the Euro is NOT the problem; it holds most probably the solution.

So we should stop talking about the euro crisis because there is no euro crisis. But there certainly is a sovereign debt crisis. Here also, balance is probably the answer. The medicine to be administered should not be so strong as to kill the patient. Thirdly, something strong should be done about the market, the sacrosanct market. May I offer the opinion that there is no such thing as a benevolent, morally superior market, which is entitled to whip member states into discipline and conformity? There are operatives, actors active on those markets, often acting as real predators anxious at making big bucks without any moral consideration whatsoever. We should not give them free rein. I am not sure that a financial transaction tax would do the trick, probably just the contrary, but we cannot allow pure speculators to destroy the very economic and financial fabric of our societies.

Of course the huge deficits must be diminished but at a rate and a pace that is sustainable and that leaves room for investment, perspective and hope.

Finally, we should anticipate the future. Too often, the remedies which are devised are modelled on the last crisis, as if the next one will be a replica of that last one. Unfortunately, that is almost never the case. To drive a car while looking only in the rear window is dangerous business.

Foremost, we need to shake ourselves free from the paralysing fear, from the doomsayers. As I said in Helsinki last week, this is not the first crisis, or upheaval or whatever you want to call it, and it most probably won’t be the last. We have weathered the previous ones; we will weather this one, provided we believe sufficiently in ourselves and spread the hope around us.

I do very much wish that this congress will be the start of just such a renewal.

And, ladies and gentlemen I have one announcement to make which points to such renewal. Our secretary General Federica Sabbati is not among us, she began her maternity leave this week and is no longer allowed to fly because she will give birth for the second time in early December. Isn’t that a beautiful, a wonderful sign of hope?

I have a last duty to perform on this stage, and that is to present Markus Löning with a farewell present. Just as me, Markus has completed his six years mandate on the ELDR Bureau and therefore is leaving. Markus has been a wonderful colleague and one of the strong holders of the ELDR bureau. Therefore, in the name of all of us, I say: Markus, thank you so much and please accept this souvenir.

Annemie Neyts-Uyttebroeck

ELDR President

MEP